April 19, 2017

A look back: Exercise Physiology and CSEP’s first 50 years

The Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology will be celebrating its 50th anniversary in 2017. A signature initiative is a celebration of the contributions of Canadian researchers to exercise physiology over the past 50 years. The objective is to highlight significant Canadian contributors and their contributions to exercise physiology, health and fitness, nutrition and gold standard publications globally as well as provide insights on future research directions in these areas. These achievements have been organized into a series of short historical communiqués on prominent Canadian contributors and will be published on a monthly basis.

Canadian Contributions to the understanding of physiology: a focus on physical activity guidelines

Tremblay MS1, Duggan M2, Adams R3, Bouchard C4, Shephard RJ5

1Healthy Active living and Obesity Research Group, Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Research Institute, Ottawa, ON

2Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology, Ottawa, ON

3Bonita Communications Inc., formerly with the Public Health Agency of Canada, Ottawa, ON

4Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Baton Rouge, LA, USA

5Retired, formerly with the University of Toronto

Background

The focus of this paper is on the history of the development of physical activity guidelines in Canada with an emphasis on the leadership contributions of Canadian Association of Sport Science (CASS) / Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology (CSEP) members. The first official Canadian Guidelines were released in 1998 (Canada’s Physical Activity Guide, Health Canada and CSEP, 1998); however, several important initiatives prior to the official establishment of CASS in 1967, and in the early years of CASS/CSEP, helped set the stage for Canada to be leaders in physical activity guideline development.

For example, in the early 1960s, under the leadership of William (Bill) Orban, the 5BX and 10BX programs were released, elevating the awareness and importance of routine exercises for healthy living (Royal Canadian Air Force, 1961; 1962). In 1966, Dr. Roy Shephard hosted an International Symposium on Physical Activity and Cardiovascular Health in Toronto, at which exercise recommendations were addressed by several speakers (Shephard, 1967; 2013). Led by former CASS President Max Howell (1968-69), a nation-wide fitness survey using the PWC170 cycle ergometer test was done on a representative sample of Canadian schoolchildren (Howell and MacNab, 1968), drawing further attention to the importance of maintaining physical fitness. Around the same time the Federal Government established three Fitness Research Units (Edmonton, Toronto and Montreal) to more formally support research in this area (Shephard, 2013).

In the 1970’s the Canadian Home Fitness Test was developed by CASS scientists (Bailey et al, 1976). This not only brought fitness testing into the homes of Canadians, but also provided the basis for the implementation of the Canada Fitness Survey in 1981 (Canada Fitness Survey, 1983a; 1983b) and subsequent Campbell’s Survey on the Well-being of Canadians in 1988 (Stephens and Craig, 1990). In addition to serving the functions of surveillance and knowledge development, these surveys provided participants with the best available recommendations to increase their physical activity and fitness level. The Canadian Fitness and Lifestyle Research Institute (CFLRI) was established in 1980 as a national research organization focused on monitoring the physical activity levels of Canadians and sharing knowledge about the importance of leading healthy, active lifestyles. The CFLRI led the Canada Fitness Survey and the Campbell’s Survey on the Well-being of Canadians with leadership from many CASS/CSEP members, notably Claude Bouchard, Gerry Glassford, Tom Stephens and Cora Craig. This sampling of important events in the earlier years of CASS/CSEP illustrates the sustained and important contributions made over the past 50 years by our society. More details on the early history of CASS/CSEP and its influential scientists can be found in a historical essay by Roy Shephard (2013).

As evidence of the health benefits of physical activity mounted, physical activity guideline efforts began to emerge from authoritative organizations and governments beginning in the middle of the 20th century (Pate et al., 1995; Pate 2007; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1996). Propelling this movement forward were four landmark Canadian conferences: the International Conference on Exercise, Fitness, and Health (Bouchard et al., 1990); the International Conference on Physical Activity, Fitness, and Health (Bouchard et al., 1994); the Dose-Response Symposium on Physical Activity and Health (Kesaniemi et al., 2001); and the Health Canada – CDC Conference on Communicating Physical Activity and Health Messages: Science into Practice (Shephard, 2002). These four conferences were led by Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology (CSEP) scientists including Claude Bouchard, Roy Shephard, John Sutton, and Norm Gledhill among others.

In 1995, the Fitness Program of Health Canada, in partnership with CSEP, reviewed the current physical activity guidance for Canadians and assessed the need for a national physical activity guide (CSEP, 1996), modelled after Canada’s Food Guide (Health Canada, 1992). The review provided clear support for the development of a national physical activity guide to help Canadians improve their health through regular physical activity. Subsequently, commissioned scientific reviews were undertaken by CSEP scientists Roy Shephard and Claude Bouchard (Shephard and Bouchard, 1996) and scientists from the Canadian Society for Psychomotor Learning and Sport Psychology (SCAPPS; Brawley and Gauvin, 1996) to inform the Guides. Ultimately, the rationale for developing a Canadian physical activity guide included substantive evidence regarding the health benefits of being physically active; identification of sedentary living as a significant public health concern; development and promotion of various recommendations for physical activity by a number of different agencies; modest existing communication of the need for physical activity; and escalation of the costs of physical inactivity (Katzmarzyk et al., 2000; Sharratt and Hearst, 2007). In 1997, the Canadian Federal–Provincial–Territorial Ministers responsible for sport, physical activity, and recreation endorsed the development of a national physical activity guide, and set a target to reduce the prevalence of physical inactivity in Canada by 10% by 2003, thus providing momentum and context for the launch of the first-ever Canada’s Physical Activity Guide (Sharratt and Hearst, 2007).

Canada’s Physical Activity Guides 1998-2002

Figure 1: Canada’s Physical Activity Guide to Healthy Active Living.

At the 1998 CSEP Conference in Fredericton, New Brunswick Canada’s Physical Activity Guide to Healthy Active Living (Figure 1; Health Canada and CSEP, 1998) was launched by CSEP President Angelo Belcastro and Health Canada representative Randy Adams. This inaugural Guide was for apparently healthy adults 20–55 years of age. The Guide recommended 20–55-year-old adults should accumulate 60 minutes of daily physical activity or 30 minutes of moderate or vigorous physical activity on at least 4 days a week. Time needed depends on effort. Specific guidelines included endurance exercises performed 4–7 d/week; flexibility exercises performed 4–7 d/week including gentle reaching, bending and stretching; and strength exercises performed 2–4 d/week.

Figure 2: Canada’s Physical Activity Guide to Healthy Active Living for Older Adults.

In 1999 (in conjunction with the International Year of the Older Adult), Canada’s Physical Activity Guide to Healthy Active Living for Older Adults was launched to address the distinct needs and capacities of adults aged >55 years (Figure 2; Health Canada and CSEP, 1999). CSEP scientists Don Paterson and David Cunningham in collaboration with the Active Living Coalition for Older Adults (ALCOA) were key leaders in the development of this guide.

Figure 3: Canada’s Physical Activity Guide for Children and Canada’s Physical Activity

Building on the success and branding of the Guides for adults and for older adults, age-specific physical activity guides for children and for youth were also developed, with CSEP scientists Michael Sharratt and Oded Bar-Or as content leaders. Once again Health Canada and CSEP partnered in the development of Canada’s Physical Activity Guide for Children (6–9 years of age) and Canada’s Physical Activity Guide for Youth (10–14 years of age) (Figure 3; Health Canada and CSEP, 2002a, 2002b). These two guides were launched in 2002 along with a variety of supporting materials (Health Canada and CSEP, 2002c; 2002d; 2002e; 2002f; 2002g; 2002h), were formally approved by Federal–Provincial–Territorial Ministers and were officially endorsed by approximately 100 national organizations. This was similar in approach to the Guides for adults and for older adults. As testimony to the timeliness and importance of the physical activity guides, at the time they were the most requested resources of the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC).

New Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines

Research on the relationship between physical activity and health expanded rapidly in the early 2000s, at least in part propelled by the presence of the physical activity guides. Accordingly, with initiative and leadership from Mark Tremblay, CSEP and PHAC, a think tank was convened in Halifax immediately preceding the 2006 CSEP Annual Scientific Conference (Figure 4). The purpose of the think tank was to review and revisit the existing scope and content of the physical activity guides. The outcomes of the pre-conference think tank were shared with the CSEP membership at a symposium at the CSEP Annual Scientific Conference. The think tank was supported through a Canadian Institutes of Health Research – Institute of Nutrition, Metabolism and Diabetes workshop grant.

Figure 4: Physical activity guideline think tank participants, Halifax, 2006. (Front row L-R: David Bassett Jr., John Spence, Bill Hearst, Audrey Giles, Jennifer Copeland; Middle row L-R: Ian Janssen, Peter Katzmarzyk, Mark Tremblay, Randy Adams, Kathleen Martin Ginis; Back row L-R: Lucie Levesque, Cora Craig, Brian Timmons, Mike Arthur, Ashlee McGuire, Larry Brawley, Dale Esliger, Robert Malina, Russ Kisby; Missing: Joe Doiron, Darren Warburton).

The 2006 think tank ignited excitement to update the physical activity guides and expand to population gaps not covered by existing guides (e.g. the early years aged 0-5 years; and the teen years aged 15-19 years). With funding from PHAC, a series of 12 background and review papers were commissioned (see lead authors in Figure 5) to form a special combined supplement of Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism and the Canadian Journal of Public Health (Figure 6). In addition to an introduction (Tremblay et al., 2007b) and future directions paper (Tremblay et al., 2007c), the special supplement included papers on: the physical activity guidelines background and development (Sharratt and Hearst, 2007; physical activity guidelines for adults (Warburton et al., 2007); physical activity guidelines for older adults (Paterson et al., 2007); physical activity guidelines for children and youth (Janssen, 2007); physical activity guidelines for preschool children (Timmons et al., 2007); physical activity guidelines for persons with a disability (Martin Ginis and Hicks, 2007); physical activity guidelines for Aboriginal Peoples (Young and Katzmarzyk, 2007); the impact of the release of the physical activity guides (Cameron et al., 2007); messaging strategies, expectations, and evaluations (Brawley and Latimer, 2007); limitations of physical activity data (Katzmarzyk and Tremblay, 2007); physical activity and inactivity profiling (Esliger and Tremblay, 2007); and new frontiers in physical activity assessment (Tremblay et al., 2007a) (available at http://www.nrcresearchpress.com/toc/apnm/32/S2E).

The 2006 think tank ignited excitement to update the physical activity guides and expand to population gaps not covered by existing guides (e.g. the early years aged 0-5 years; and the teen years aged 15-19 years). With funding from PHAC, a series of 12 background and review papers were commissioned (see lead authors in Figure 5) to form a special combined supplement of Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism and the Canadian Journal of Public Health (Figure 6). In addition to an introduction (Tremblay et al., 2007b) and future directions paper (Tremblay et al., 2007c), the special supplement included papers on: the physical activity guidelines background and development (Sharratt and Hearst, 2007; physical activity guidelines for adults (Warburton et al., 2007); physical activity guidelines for older adults (Paterson et al., 2007); physical activity guidelines for children and youth (Janssen, 2007); physical activity guidelines for preschool children (Timmons et al., 2007); physical activity guidelines for persons with a disability (Martin Ginis and Hicks, 2007); physical activity guidelines for Aboriginal Peoples (Young and Katzmarzyk, 2007); the impact of the release of the physical activity guides (Cameron et al., 2007); messaging strategies, expectations, and evaluations (Brawley and Latimer, 2007); limitations of physical activity data (Katzmarzyk and Tremblay, 2007); physical activity and inactivity profiling (Esliger and Tremblay, 2007); and new frontiers in physical activity assessment (Tremblay et al., 2007a) (available at http://www.nrcresearchpress.com/toc/apnm/32/S2E).

Figure 5: Participants at the writing retreat for the Special Supplement, Kananaskis, March, 2007. (Front row L-R: Lori Zehr, Audrey Hicks, Amy Latimer, Roy Shephard, Ian Janssen, Darren Warburton, Mary Duggan; Back row L-R: Larry Brawley, Don Paterson, Bill Hearst, Mike Sharratt, Randy Adams, Dale Esliger, Peter Katzmarzyk, John Spence, Kue Young, Brian Timmons, Roxanne Poirier, Ashlee McGuire; Missing: Christine Cameron, Mark Tremblay)

An International Consensus Conference on “Advancing the Future of Physical Activity Measurement and Guidelines” was hosted by CSEP and PHAC in Kananaskis, Alberta on January 14-16, 2009. The conference was Chaired by Mark Tremblay and included the engagement of an independent Expert Assessment Panel consisting of Antero Kesaniemi (Finland; Chair), Bruce Reeder (Canada), Thorkild Sorensen (Denmark); Chris Riddoch (United Kingdom), and Steve Blair (United States). The tasks of the Expert Assessment Panel were to read background documents and reviews, participate in pre-conference meetings, attend and participate in the conference, listen to presentations and discussions, ask questions and seek clarity as required, work as a group to achieve consensus on recommended physical activity guidelines for Canadians based on evidence presented, agree on level of evidence informing the physical activity guidelines, and prepare a consensus statement for publication. Additional international experts were invited to attend and participate in the Conference to avoid duplication of effort, promote consistency and harmonization of physical activity guidelines internationally, and facilitate collaborations, research initiatives and international cross-fertilization. Process experts in the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research Evaluation (AGREE II; Brouwers et al., 2010a, 2010b, 2010c) were engaged throughout the guideline development process. Participants in the consensus conference are in Figure 7.

In preparation for the International Consensus Conference additional systematic reviews were commissioned to adhere to established clinical practice guidelines and were subsequently published in a thematic issue of the International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity along with a process paper and the Expert Assessment Panel paper (Janssen and LeBlanc, 2010; Kesäniemi et al., 2010; Latimer et al., 2010; Paterson and Warburton, 2010; Rhodes and Pfaeffli, 2010; Tremblay et al., 2010; Warburton et al., 2010; available at http://www.biomedcentral.com/collections/canada-physical-activity).

Figure 7: Participants in the International Consensus Conference, Kananaskis, January, 2009. (Front L-R: Bill Haskell, Roy Shephard, Steve Blair, Larry Brawley, Rick Troiano, Christine Cameron, Michelle Kho, Ryan Rhodes, Vanessa Candeias, Ashlee McGuire, Julie Pinard, Michelle Mottola, Kathleen Martin Ginis, Sarah Charlesworth, I-Min Lee, Isabel Romero, Mary Duggan, Randy Adams, Halina Cyr, Stuart Biddle, Chris Riddoch, Trevor Shilton, Rod Dishman; Middle L-R: Angelo Belcastro, Amy Latimer, Brian MacIntosh, Lori Zehr, Thorkild Sorensen, Russ Pate, Antero Kesaniemi, Van Hubbard; Back: Norm Gledhill, Don Paterson, Bruce Reeder, Mark Tremblay, Darren Warburton, Art Salmon, Peter Katzmarzyk, Ian Janssen); Missing: Kelly Murumets, Jim Stone, Andrea Tricco)

The “new” Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines were published with detailed and transparent explanation of the process (Tremblay et al., 2011c) and were launched in January, 2011 along with supporting materials developed and promoted by CSEP, ParticipACTION, the Healthy Active Living and Obesity Research Group at the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Research Institute (HALO), and others. The new Guidelines were for children aged 5-11 years; youth aged 12-17 years; adults aged 18-64 years; and older adults aged 65+ years. In 2012, Physical Activity Guidelines for the Early Years (aged 0-4 years) were launched (Tremblay et al., 2012b), also informed by published systematic review evidence (Timmons et al., 2012), completing guidelines for all age groups. Many CSEP members were involved in the guideline development, with notable contributions from Brian Timmons (early years), Ian Janssen (children and youth), Darren Warburton (adults) and Don Paterson (older adults). Mary Duggan from the CSEP office was instrumental in getting the new guidelines completed and launched. The relatively new partnership with ParticipACTION was mutually beneficial and the start of many more collaborations moving forward.

Messaging

An important new adjunct to the guidelines of this period was the development of evidence-based guidelines messaging. Few validated guidelines exist for developing messages in health promotion practice. Working in partnership with SCAPPS members, ParticipACTION and the Public Health Agency of Canada, CSEP and the Physical Activity Guidelines Messaging Recommendation Workgroup developed the first evidence-informed recommendations for constructing and disseminating messages supplementing physical activity guidelines (Latimer-Cheung et al., 2013). This also represented the first time that international standards for guideline development (i.e., AGREE II) were used in the creation of practical recommendations aimed to inform health promotion and public health practice. These principles continue to be applied by CSEP and others to subsequent guideline development initiatives.

Physical Activity Guidelines for Special Populations

Figure 8: Physical Activity Guidelines for Adults with Spinal Cord Injury.

Concurrent with the development of new physical activity guidelines for the general “apparently healthy” population, efforts were underway to provide guidance to Canadians with a disability and chronic disease, pregnant women and Indigenous Canadians.

In 2008, with leadership by Randy Adams and Mark Tremblay several meetings were held with the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch of the Canadian Government in an attempt to develop tailored Physical Activity Guidelines/Guides for First Nations, Inuit and Metis groups. Despite establishing and agreeing upon official Terms of Reference for a Physical Activity Guide for First Nations, Inuit & Métis (PAG-FNIM) Advisory Committee, efforts in this regard did not proceed.

In 2011, SCI Action Canada published the first evidence-informed Physical Activity Guidelines for Adults with Spinal Cord Injury (Figure 8; Martin Ginis et al., 2011). The development of these guidelines was initiated in 2009, led by Kathleen Martin Ginis and Audrey Hicks, and harmonized with the process that CSEP had been using to develop guidelines for the general population. CSEP endorsed the guidelines and agreed to assist with their promotion and dissemination.

Figure 9: Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines for Adults with Multiple Sclerosis.

Commencing in November 2011, CSEP provided stakeholder support and dissemination to principal investigators Amy Latimer-Cheung, Kathleen Martin Ginis and Audrey Hicks to develop the first evidence-informed Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines for Adults with Multiple Sclerosis (Latimer-Cheung, et al. 2013). Over 2.5 million people worldwide are living with multiple sclerosis (MS); a large proportion is in Canada and most adults with MS are inactive and have become deconditioned. The guideline development process followed the same rigorous international standards used to develop the physical activity guidelines for the general population (i.e., AGREE II) and established that those with mild to moderate symptoms benefit from regular physical activity at a lower intensity and shorter duration. In 2012 CSEP published the Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines for Adults with Multiple Sclerosis and throughout 2013, CSEP worked with ParticipACTION and the MS Society of Canada to develop associated evidence-based messaging and supplementary materials for practitioners and patients (see Figure 9).

Recognized for its continuing leadership in guideline and guidelines messaging development, in September 2013 the Society and a number of CSEP members were invited to participate on a consensus panel to develop a consensus statement on physical activity and dementia using evidence from several published systematic reviews. These efforts were led by the Ontario Brian Institute who wanted to know whether physical activity could help prevent Alzheimer’s disease and/or be beneficial for managing symptoms and complications associated with Alzheimer’s. The consensus panel determined that it would be appropriate to utilize the AGREE II protocol to develop an evidence-based message statement to encourage the use physical activity to prevent and manage Alzheimer’s disease, in the absence of sufficient current evidence to develop a formal guideline or prescription (Martin Ginis et al., 2017).

In 2015 Michelle Mottola secured a CIHR grant to update the 2003 Joint SOGC/CSEP Clinical Practice Guideline: Exercise in Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period (Davies et al., 2003). CSEP is providing stakeholder support and dissemination assistance to principal investigators Michelle Mottola, Margie Davenport and Stephanie-May Ruchat to review the evidence on the effects of physical activity on maternal health and fetal health, and to subsequently develop updated guidelines. A number of CSEP members are part of the consensus panel whose work is partway through the guideline development process.

Canadian Sedentary Behaviour Guidelines

In addition to setting a very high standard for physical activity guideline development, CSEP scientists were the first in the world to develop and launch clinical practice guidelines specifically for sedentary behaviours, separate and distinct from physical activity. Following a similar robust and transparent process used for the physical activity guideline development, CSEP scientists completed and published systematic reviews of the evidence (LeBlanc et al., 2012; Tremblay et al., 2011a) available to inform Canadian Sedentary Behaviour Guidelines for Children and Youth (aged 5-17 years)(Tremblay et al., 2011b) and Canadian Sedentary Behaviour Guidelines for the Early Years (aged 0-4 years) (Tremblay et al., 2012c). CSEP launched these world first guidelines in February, 2011 (children and youth) and March, 2012 (early years), again in partnership with ParticipACTION and HALO. Figure 10 shows the participants involved in this process. During that year the Sedentary Behaviour Research Network (SBRN), an international group of researchers and others with an interest in this emerging science (established by Mark Tremblay and numerous CSEP members), spearheaded an initiative to encourage standardization the terms “sedentary behaviour” and “physical inactivity” in research and associated publications (Sedentary Behaviour Research Network, 2012).

Figure 10: Guideline development panel for the first Canadian Sedentary Behaviour Guidelines for Children and Youth. (Front L-R: Rachel Colley, Mark Tremblay, Ian Janssen, Kelly Murumets; Back L-R: Val Carson, Ulf Ekelund, Tony Okely, Tom Warshawski, Mary Duggan, Allana LeBlanc)

World’s First 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for Children and Youth

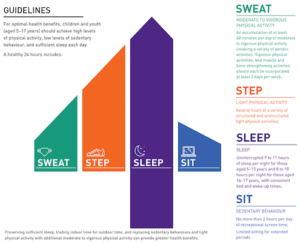

In 2014, again being world leaders, CSEP’s Guideline Coordination Subcommittee began work on the development of the Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for Children and Youth: An Integration of Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour, and Sleep (Tremblay et al., 2016b). This paradigm shifting effort was a partnership among CSEP, HALO, ParticipACTION, the Conference Board of Canada and PHAC (Tremblay et al., 2016a). The integration of movement behaviours throughout the whole day brings the energy-out side of the energy balance equation in synchrony with the energy-in side (i.e., all food groups contained within food guides). Although much more complex, the new guidelines were informed by multiple systematic reviews (Carson et al., 2016a; Chaput et al., 2016; Poitras et al., 2016; Saunders et al., 2016) as well as novel compositional analyses (Carson et al., 2016b). The participants in the guideline development panel are in Figure 11. Extensive stakeholder consultations and focus groups meetings were held to further inform the guidelines and their dissemination (Faulkner et al., 2016; Tremblay et al., 2016b). The implications of these new guidelines to stakeholder organizations and active living practitioners were also studied (Latimer-Cheung et al., 2016). In June, 2016 these guidelines, the newest and most progressive member of the CSEP guidelines family, were publicly released. The guidelines are presented through their iconography in Figure 12 (Tremblay et al., 2016b).

Figure 11: Participants in the guideline development panel for the Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for Children and Youth. (Front L-R: Sophie Rodenburg, Audrey Phillips, Gaya Jayaraman, Katherine Janson, Mark Tremblay; Second row L-R: Veronica Poitras, Sarah Connor Gorber, Casey Gray, Amy Latimer, Thy Dinh, Val Carson, Travis Saunders, Lori Zehr, Tim Olds; Third row L-R: Gareth Stratton, Russ Pate, Reut Gruber, Mary Duggan, Margaret Sampson; Back row L-R: Peter Katzmarzyk, Shelly Weiss, Guy Faulkner, Tony Okely, Ian Janssen, Rachel Rodin, Jean-Philippe Chaput; Missing: Michelle Kho, Claire LeBlanc, Jim Stone)

Contributions Beyond Canada

CSEP guideline development processes and member experiences have had an impact beyond Canada. For example, CSEP member Mark Tremblay was an international advisor for the development and/or release of the Australian (2014), United Kingdom (2011), German (2017) and World Health Organization (2010) Physical Activity Guidelines. Peter Katzmarzyk has been part of the expert panel involved in the development of U.S. Physical Activity Guidelines. Mark Tremblay, with U.S. Guideline development leader Bill Haskell, co-authored a book chapter outlining the detailed process necessary for making robust physical activity guidelines (Tremblay and Haskell, 2012a). CSEP is contacted regularly by countries throughout the world for advice on physical activity guideline development.

The Future

Figure 12: Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for Children and Youth: An Integration of Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour, and Sleep.

The future of healthy movement guideline development in Canada is focused on a whole day approach and the development of Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for all ages, integrating physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and sleep. The child and youth guidelines (ages 5-17 years) are complete and released (Tremblay et al., 2016), the early years guidelines (ages 0-4 years) are under development (expected release in September, 2017), and plans for adult and older adult guidelines are underway. The implications and opportunities for CSEP Certified Professionals (Latimer-Cheung et al., 2016) with this whole day approach are exciting, numerous and transformative.

Summary

In summary, for the past 50 years CASS/CSEP scientists (often in collaboration with SCAPPS colleagues) have been at the forefront of healthy movement guideline development, both in Canada and globally. The contributions of these guidelines to public health efforts in Canada are significant, substantial and important. The CSEP journal Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism has published many of the guideline-related papers after peer-review and many of these papers are among the highly cited list for the journal. CSEP and its members should be proud of this legacy!

References

Australian Government, Department of Health. 2014. Australia’s Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour Guidelines for ages 5-17 years. Commonwealth of Australia, 2014.

Bailey, D., Shephard, R.J., Mirwald, R. Validation of a self-administered test of cardio-respiratory fitness. Can. J. Appl. Sport Sci. 1:67-78, 1976.

Bouchard, C., Shephard, R.J., Stephens, T., Sutton, J.R., and McPherson, B.D. Editors). 1990. Exercise, fitness, and health: a consensus of current knowledge. Human Kinetics, Champaign, Ill.

Bouchard, C., Shephard, R.J., and Stephens, T. (Editors). 1994. Physical activity, fitness, and health: international proceedings and consensus statement. Human Kinetics, Champaign, Ill.

Brawley, L.R., and Gauvin, L. 1996. Psychological outcomes and social psychological principles for the design of the Canadian Guide for Healthy Physical Activity. Review document prepared for CSEP, with funding from Health Canada, in preparation of Canada’s Physical Activity Guide for Healthy Active Living [online]. Available from http://www.csep.ca.

Brawley, L.R., and Culos-Reed, N. 1999. The physical activity of children and youth: outcomes of participation and scientific summary of psychosocial outcomes. Review document prepared for CSEP, with funding from Health Canada, in preparation of Canada’s Physical Activity Guide for Children and Youth [online]. Available from http://www.csep.ca.

Brawley, L.R., and Latimer, A. 2007. Physical activity guides for Canadians: messaging strategies, realistic expectations for change, and evaluation. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 32(Suppl. 2E): S170-S184.

Brouwers, M.C., Kho, M.E., Browman, G.P., Burgers, J.S., Cluzeau, F., Feder, G., et al.; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. 2010a. AGREE II: Advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ, 182(18): E839–E842.

Brouwers, M.C., Kho, M.E., Browman, G.P., Burgers, J.S., Cluzeau, F., Feder, G., et al.; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. 2010b. Development of the AGREE II, part 1: performance, usefulness and areas for improvement. CMAJ, 182(10): 1045–1052.

Brouwers, M.C., Kho, M.E., Browman, G.P., Burgers, J.S., Cluzeau, F., Feder, G., et al.; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. 2010c. Development of the AGREE II, part 2: assessment of validity of items and tools to support application. CMAJ, 182(10):E472–E478.

Cameron, C., Craig, C.L., Bull, F.C., and Bauman, A.E. 2007. Canada’s physical activity guides: has their release had an impact? Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 32(Suppl. 2E):S161-S169.

Canada Fitness Survey. A User’s Guide to CFS Findings. Ottawa: Canada Fitness Survey, 1983a.

Canada Fitness Survey. Fitness and lifestyle in Canada. Ottawa: Canada Fitness Survey, 1983b.

Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. 1996. Canada’s Physical Activity Guide — synthesis of substantive content for the Guide based on the scientific review process. Document summary in preparation of Canada’s Physical Activity Guide for Healthy Active Living [online]. Available from http://www.csep.ca.

Carson, V., Hunter, S., Kuzik, N., Gray. C.E., Poitras, V.J., Chaput, et al. 2016a. Systematic review of sedentary behaviour and health indicators in school-aged children and youth: an update. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 41(6 suppl.3):S240-S265.

Carson, V., Tremblay, M.S., Chaput, J-P., Chastin, S.F.M. 2016b. Associations between sleep duration, sedentary time, physical activity, and health indicators among Canadian children and youth using compositional analyses. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 41(6 suppl.3):S294-S302.

Chaput, J-P., Gray, C.E., Poitras, V.J., Carson, V., Gruber, R., Olds, T., et al. 2016. Systematic review of the relationships between sleep duration and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 41(6 suppl.3):S266-S282.

Davies, G.A.L., Wolfe, L.A., Mottola, M.F., MacKinnon, C. 2003. Joint SOGC/CSEP Clinical Practice Guideline: Exercise in Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period. Can. J. Appl. Physiol. 28(3):329-341.

Esliger D.W., Tremblay, M.S. 2007. Physical activity and inactivity profiling: the next generation. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 32(suppl.2E):S195-S207.

Faulkner, G., White, L., Raizi, N., Latimer-Cheung, A.E., Tremblay, M.S. 2016. Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for Children and Youth: Exploring the perceptions of stakeholders regarding their acceptability, barriers to uptake, and dissemination. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 41(6 suppl.3):S303-S310.

Health Canada. 1992. Canada’s Food Guides from 1942 to 1992. http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/fn-an/food-guide-aliment/context/fg_history-histoire_ga-eng.php#fnb24 (accessed January 22, 2017).

Health Canada and the Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. 1998. Canada’s physical activity guide to healthy active living. Cat. No. H39-429/1998-1E. Health Canada, Ottawa, ON.

Health Canada and the Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. 1999. Canada’s physical activity guide to healthy active living for older adults. Cat. No. H39-429/1999-1E. Health Canada, Ottawa, ON.

Health Canada and the Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. 2002a. Canada’s physical activity guide for youth. Cat. No. H39-611/2002-1E. Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada, Ottawa, ON.

Health Canada and the Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. 2002b. Canada’s physical activity guide for children. Cat. No. H39-611/2002-2E. Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada, Ottawa, ON.

Health Canada and the Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. 2002c. Family guide to physical activity for youth 10–14 years of age. Cat. No. H39-646/2002-2E. Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada, Ottawa, ON.

Health Canada and the Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. 2002d. Family guide to physical activity for children 6–9 years of age. Cat. No. H39–646/2002–1E. Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada, Ottawa, ON.

Health Canada and the Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. 2002e. Teacher’s guide to physical activity for youth 10–14 years of age. Cat. No. H39-647/2002-2E. Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada, Ottawa, ON.

Health Canada and the Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. 2002f. Gotta move! Magazine for children 6–9 years of age. Cat. No. H39-648/2002-1E. Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada, Ottawa, ON.

Health Canada and the Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. 2002g. Let’s get active! Magazine for youth 10–14 years of age. Cat. No. H39-648/2002-2E. Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada, Ottawa, ON.

Health Canada and the Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. 2002h. Teacher’s guide to physical activity for children 6–9 years of age. Cat. No. H39-647/2002-1E. Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada, Ottawa, ON.

Howell, M.L., MacNab, R.B.J. The physical work capacity of Canadian children 7-17 years. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Association for Health, Physical Education & Recreation, 1968.

Janssen, I. 2007. Physical activity guidelines for children and youth. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 32(Suppl. 2E):S109-S121.

Janssen, I., and LeBlanc, A.G. 2010. Systematic review of the health benefits of physical activity and fitness in school-aged children and youth. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 7: 40.

Katzmarzyk, P.T., Gledhill, N., Shephard, R.J. 2000.The economic burden of physical inactivity in Canada. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 162 (11):1435-1440.

Katzmarzyk, P.T., Tremblay, M.S. 2007. Limitations of Canada’s physical activity data: implications for monitoring trends. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 32(suppl.2E):S185-S194.

Kesäniemi, Y.A., Danforth, E., Jensen, M.D., Kopelman, P.G., Lefebvre, P., Reeder, B.A. 2001. Dose-response issues concerning physical activity and health: an evidence-based symposium. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 33:S351–S358.

Kesäniemi, A., Riddoch, C.J., Reeder, B., Blair, S., and Sørenson, T. 2010. Advancing the future of physical activity guidelines in Canada: an independent expert panel interpretation of the evidence. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 7: 41.

Latimer, A.E., Brawley, L.R., and Bassett, R.L. 2010. A systematic review of three approaches for constructing physical activity messages: what messages work and what improvements are needed? Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 7: 36.

Latimer-Cheung, A.E., Rhodes, R.E., Kho, M.E., Tomasone, J.R., Gainforth, H.L., Kowalski, K., et al., and The Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines Messaging Recommendation Workgroup. 2013. Evidence-informed recommendations for constructing and disseminating messages supplementing the new Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines. BMC Public Health 13:419.

Latimer-Cheung, A.E., Copeland, J.L., Fowles, J., Zehr, L., Duggan, M., Tremblay, M.S. 2016. The Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for Children and Youth: Implications for practitioners, professionals, and organizations. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 41(6 suppl.3):S328-S335.

LeBlanc, A.G., Spence, J.C., Carson, V., Connor Gorber, S., Dillman, .C, Janssen, I., et al. 2012. Systematic review of sedentary behaviour and health indicators in the early years (aged 0-4 years). Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 37:753-772.

LeBlanc, A.G., Berry, T., Deshpande, S., Duggan, M., Faulkner, G., Latimer-Cheung, A.E., et al. 2015. Knowledge and awareness of Canadian Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour Guidelines: a synthesis of existing evidence. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 40:716-724.

Martin Ginis, K.A., Hicks, A.L. 2007. Considerations for the development of a physical activity guide for Canadians with physical disabilities. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 32(Suppl. 2E): S135-S147.

Martin Ginis, K.A., Hicks, A., Latimer, A.E, Warburton, D.E.R, Bourne, C., Ditor, D.S., et al. 2011. The development of evidence-informed Physical Activity Guidelines for People with Spinal Cord Injury. Spinal Cord 1-9. doi: 10.1038/sc.2011.63.

Martin Ginis, K.A., Heisz, J., Spence, J.C., Clark, I.B., Antflick, J., Ardern, C.I., et al. 2017. Formulation of evidence-based messages to promote the use of physical activity to prevent and manage Alzheimer’s disease. BMC Public Health. In Press. DOI 10.1186/s12889-017-4090-5.

Pate, R.R., Pratt, M., Blair, S.N., Haskell, W.L., Macera, C.A., Bouchard, C., Buchner, D., Ettinger, W., Heath, G.W., King, A.C., Kriska, A., Leon, A.S., Marcus, B.H., Morris, J., Paffenbarger, R.S., Patrick, K., Pollock, M.L., Rippe, J.M., Sallis, J., Wilmore, J.H. Physical activity and public health: A recommendation from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Sports Medicine. JAMA 273:402-407, 1995.

Pate, R.R. 2007. Historical perspectives on physical activity, fitness, and health. In Physical activity and health. Edited by C. Bouchard, S.N. Blair and W.L. Haskell. Human Kinetics Inc., Champaign, Ill. pp. 21–36.

Paterson, D.H., Jones, G.R., and Rice, C.L. 2007. Ageing and physical activity: evidence to develop exercise recommendations for older adults. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 32(Suppl. 2E):S69-S108.

Paterson, D.H., and Warburton, D.E.R. 2010. Physical activity and functional limitations in older adults: a systematic review related to Canada’s Physical Activity Guidelines. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 7: 38.

Poitras, V.J., Gray, C.E., Borghese, M.M., Carson, V., Chaput, J-P., Janssen, I., et al. 2016. Systematic review of the relationships between objectively measured physical activity and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 41(6 suppl.3):S197-S239.

Rhodes, R.E., and Pfaeffli, L.A. 2010. Mediators of physical activity behaviour change among adult non-clinical populations: a review update. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 7: 37.

Royal Canadian Air Force. 5BX Plan for Physical Fitness. Queen’s Printer, 1961.

Royal Canadian Air Force. XBX Plan for Physical Fitness. Queen’s Printer, 1962.

Saunders, T.J., Gray, C.E., Poitras, V.J., Chaput, J-P., Janssen, I., Katzmarzyk, P.T., et al. 2016. Combinations of physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep: relationships with health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 41(6 suppl.3):S283-S293.

Sedentary Behaviour Research Network. 2012. Letter to the Editor: Standardized use of the terms “sedentary” and “sedentary behaviours”. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 37(3): 540-542.

Sharratt, M., Hearst, W. 2007. Canada’s physical activity guides: background, process, and development. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 32(Suppl. 2E):S9-S15.

Shephard, R.J. Guest Editor. Proceedings of the International Symposium on Physical Activity and Cardiovascular Health. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 96:695-915, 1967.

Shephard, R.J., and Bouchard, C. 1996. Canada’s Guide to Healthy Physical Activity – Biological outcomes. Review document prepared for CSEP, with funding from Health Canada, in preparation of Canada’s Physical Activity Guide for Healthy Active Living [online]. Available from http://www.csep.ca.

Shephard, R.J. 2002. Whistler 2001: a Health Canada – CDC conference on ‘‘Communicating physical activity and health messages: Science into practice.’’. Am. J. Prev. Med. 23: 221–225.

Shephard, R.J. The first fifty years: A personal perspective on the history of Canadian Exercise Physiology. Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology website, September 2013. http://www.csep.ca/view.asp?ccid=545 (accessed April 10, 2017).

Stephens, T., Craig, C.L. The Well-Being of Canadians: Highlights of the 1988 Campbell’s Survey. Ottawa: Canadian Fitness and Lifestyle Research Institute, 1990.

Timmons, B.W., Naylor, P.-J., and Pfeiffer, K.A. 2007. Physical activity for pre-school children — how much and how? Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 32(Suppl. 2E):S122-S134.

Timmons, B.W., LeBlanc, A.G., Carson, V., Connor Gorber, S., Dillman, C., Janssen, I., et al. 2012. Systematic review of physical activity and health in the early years (aged 0-4 years). Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 37:773-792.

Tremblay, M.S., Esliger, D.W., Tremblay, A., Colley, R.C. 2007a. Incidental movement, lifestyle-embedded activity and sleep: new frontiers in physical activity assessment. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 32(suppl.2E):S208-S217.

Tremblay, M.S., Shephard, R.J., Brawley, L.R. 2007b. Research that informs Canada’s Physical Activity Guides: an introduction. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 32(suppl.2E):S1-S8.

Tremblay, M.S., Shephard, R.J., Brawley, L., Adams, R., Cameron, C., Craig, C.L., et al. 2007c. Physical activity guidelines and guides for Canadians: facts and future. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 32(Suppl. 2E): S218-S224.

Tremblay, M.S., Kho, M.E., Tricco, A.C., Duggan, M. 2010. Process description and evaluation of Canadian physical activity guidelines development. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 7:42.

Tremblay, M.S., LeBlanc, A.G., Kho, M.E., Saunders, T.J., Larouche, R., Colley, R.C., et al. 2011a. Systematic review of sedentary behaviour and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 8:98.

Tremblay, M.S., LeBlanc, A.G., Janssen, I., Kho, M.E., Hicks, A., Murumets, K., et al. 2011b. Canadian Sedentary Behaviour Guidelines for School-aged Children and Youth. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 36(1):59-64.

Tremblay, M.S., Warburton, D.E.R., Janssen, I., Paterson, D.H., Latimer, A.E., Rhodes, R.E., et al. 2011c. New Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 36(1):36-46.

Tremblay, M.S. Haskell, W.L. 2012a. From science to physical activity guidelines. In C. Bouchard, S.N. Blair and W.L. Haskell (Eds.), Physical Activity and Health, 2nd Edition. Human Kinetics Publishers. p. 359-378.

Tremblay, M.S., LeBlanc, A.G., Carson, V., Choquette, L., Connor Gorber, S., Dillman, C., et al. 2012b. Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines for the Early Years (aged 0-4 years). Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 37:345-356.

Tremblay, M.S., LeBlanc, A.G., Carson, V., Choquette, L., Connor Gorber, S., Dillman, C., et al. 2012c. Canadian Sedentary Behaviour Guidelines for the Early Years (aged 0-4 years). Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 37:370-380.

Tremblay, M.S., Carson, V., Chaput, J-P. 2016a. Introduction to the Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for Children and Youth: An Integration of Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour, and Sleep. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 41(6 suppl.3):iii-iv.

Tremblay, M.S., Carson, V., Chaput, J-P., Connor Gorber, S., Dinh, T., Duggan, M., et al. 2016b. Canadian 24-hour Movement Guidelines for Children and Youth: An Integration of Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour, and Sleep. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 41(6 suppl.3):S311-S327.

United Kingdom. 2011. Start Active, Stay Active. A report on physical activity for health from the four home countries’ Chief Medical Officers. Repartment of Health, London, U.K..

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 1996. Physical activity and health: a report of the Surgeon General. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Atlanta, Ga. pp. 9–60.

Warburton, D., Katzmarzyk, P.T., Rhodes, R.E., and Shephard, R.J. 2007. Evidence-informed physical activity guidelines for Canadian adults. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 32(Suppl. 2E):S16-S68.

Warburton, D.E.R., Charlesworth, S., Ivey, A., Nettlefold, L., and Bredin, S.S.D. 2010. A systematic review of the evidence for Canada’s Physical Activity Guidelines for Adults. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 7(1): 39.

World Health Organization. 2010. Global recommendations on physical activity for health. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Young, T.K., and Katzmarzyk, P.T. 2007. Physical activity in Aboriginal people of Canada. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 32(Suppl. 2E):S148-S160.